Rex Packwood Vamooses

Art Welch had always been a trouble maker. That is to say he had a ready supply for those who made it their business to find it. For nearly a decade he had run afoul of the local puritans that were pushing the religiously spirited Blue Laws of the time. Arrested for selling newspapers on a Sunday in 1902, he was no stranger to the mechanisms of law. His father, Robert Welch, a saloon keeper from Ireland, had raised him within the habiliments of Old West in the borderlands between vice and justice.

This Pantitorium venture of Art’s was a copy of other such establishments dotting the landscape of the frontier towns. These were essentially early draft versions of the laundromat while a bit more robust: a centrally located storefront (catered to men) where one could get clothes pressed, read the latest papers, maybe buy a cigar or get a shave. In 1905 a person in Iowa probably owned only one or two sets of clothes, and a person living in the city would not have access to traditional cleaning regiments like the creek and a clothesline. Those living in early tenements or rooming in flats were want for basics like running water or windows. There was a necessity to having your clothes pressed or having your face shaved. Visit the popular Turkish Baths around the corner and experience the rare thrill of submerging your body in hot clean water. An unheard of pleasure on the prairie.

Shops like Art Welch’s Panitorium functioned as a members only affair conferring a $1 a month charge for membership. Part barbershop, part news stand, part necessary hygiene ritual. At its heart: a place for cavorting under pretense during a time in which cavorting was over-scrutinized by a puritanical mob. Any given Panitorium would exist on a scale from ‘legitimate business’ to ‘vice hall under disguise’. Where Art Welch fell on this scale we will have to guess.

This is a tale of barbers

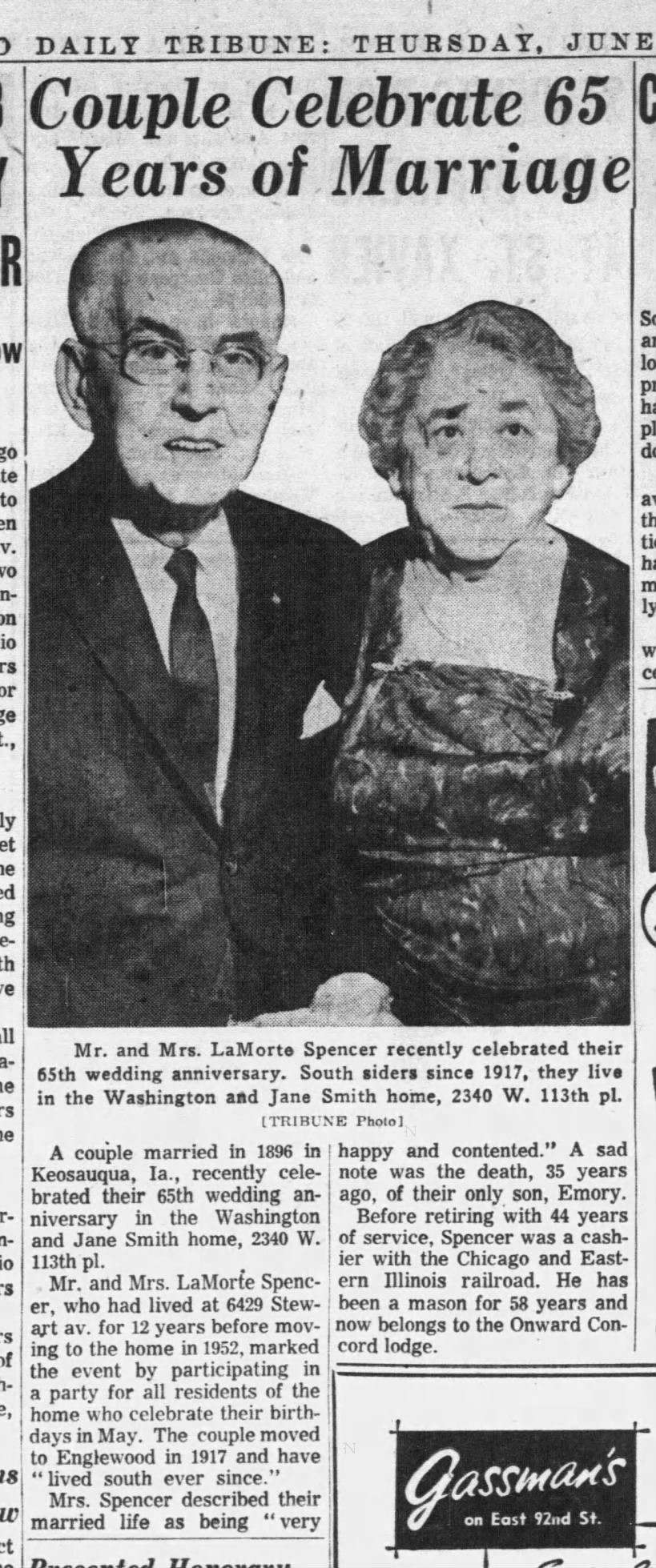

L. H. Spencer – LaMorte Holley – here was a straight shooter. A skinny man with Dracula features that match his biblical name which means “Death”. He was born about 1875 in Brooklyn, Iowa, a small stack of bricks nestled between two little creeks and midway through the morass between Des Moines and Iowa City. He married his true love and had a child down in Keosauqua before they relocated to the commerce and cultural hub of Muscatine.

Muscatine fit into the lower end of the Matryoshka of vicey urban centers scattered along the highways of yesteryear. In 1905 it was like a gateway drug to the city proper. Just big enough to get in trouble but too small to get lost. Snug against the Mississippi River it lazes across the water from Illinois, one of several divine crossroads where the old river marries the new iron god. A shallow pool of vice. A doorway. An infection.

LaMorte appears in the newspapers in Muscatine starting in 1900; over a dozen published references outline him as an active member of the local Barbers Union and supporter of trade unionism. He’s not just a good barber, LaMorte is a master barber representing the interests of other barbers.

This is a tumultuous time for the Knights of the Razor. Barbering proves to be a unique case study in organized labor and plays upon notes from parallel symphonies: secret societies, the mafia, the Wobblies, and that ravenous herd of morality police eventually responsible for prohibition.

For generations untold, “The Tonsorial Arts” had been passed from master to apprentice in an enduring and occult practice. They called themselves knights for that very reason. It could take years of apprenticeship to become a barber and only the steadiest of hands would make the cut. To even find a Master willing to take one as a student would be a challenge.

Yet now these Knights were threatened by a hydra of foes: the opponents of organized labor and the strange bedfellows they brought; maverick barbers who refused Union rule; puritans in Church and State that would seek to regulate the trade for ill; and of greatest concern, newly minted “barbers” being cranked out of six-week schools in Chicago competing with wizardly lifers with decades of apprenticeship.

The Moler Barber College being the chief culprit in a rogues gallery of lesser schools hawking the same education. Become a barber in six week course. Unannounced like an earthquake the number of barbers rose exponentially being delivered from the big cities to the frontier towns by the steam headed demigod which came to dominate the endless nothing.

This was a time of colliding definitions. On the edge of the frontier, what had been isolated and idyllic farm kingdoms were assaulted by the approaching machinations of the Eastern factories. The upset of the “American dream” from petty fiefdom to free labor. The people alive remembered the kinetic reality of the Civil War. There were a million lost souls scrambling across the plains in search of their ships-yet-come-in. Long on Gatsbys and short on Greatness.

To be a barber in Iowa in 1900 was to scrap with socialists, capitalists and puritans. The socialists wanted to regulate your income. The capitalists wanted to embezzle your income. The puritans wanted to limit your work hours and availability vice trades. Your allies were the prostitutes, opium peddlers, cigar and paper salesmen. The prostitutes were under attack by the same puritans and often worked similar late hours to the barber shop. The opium peddlers the same and often on the same block. The cigar and paper salesmen were somehow caught up in the same anti-vice dragnet for the guilt of selling on the Sabbath.

The theater of this battle was the saloon and the barbershop; every bit a saloon without a bar,

If you gaze hard enough you can see the ingredients of Prohibition begin to catalyze. Here is a typical screed printed in 1900 in Muscatine and an introduction to the Mulct law:

The Mulct law in Iowa made it so that saloons were default illegal unless 65% of a county or town were to vote in favor of having them. The above posting reveals a terrible oppostion to any relaxation of the anti-saloon laws. To police a saloon was to police the bodies that inhabit it, the vices or unsavory practices they bring with them.

This same cast of self proclaimed morality regulators caused a stir in 1902 shutting down all business on Sundays. Note below that this is when Art Welch is arrested – he deigned to sell newspapers on the Sabbath.

Through this period in Iowa social definitions are fighting for dominance in the drying ink and parchment of post-Civil War, pre-World War America. The people of Iowa can’t tell where vice or virtue begin or end.

The State, now a powerhouse of social change, provided a vehicle for those who would regulate society – both the heroic and the villainous. So many special interest groups drawn from the well, it was a thousand hand slap; the attacks come from all angles and sources. A dozen dogs fighting over a single chop. Everyone wanted a law.

The Barbers wanted a law to regulate the trade by requiring tests and licensing, believing it would limit the ability of the new schools to turn out the poorly trained barbers that had become cheap competition. This was of great concern; the necessity of the barber and the long years of training required had resulted in a high and steady wage for a learned swipe. Now the trains were depositing an endless stream of school barbers ready to accept lower wages and worse hours, or the even greater sin of working nonunion shops.

The chivalric barbers felt the school barbers were largely to blame for the spread of Tuberculosis – notoriously associated with the poor hygeine of the sloppy tonsorialist. This put yet more pressure on the State to regulate the industry against the White Plague.

Regulation would be a double edged sword for barbers – their shops were often gateways to other vice, and barbers were the beneficiaries thereof. A barber might compel the state to license the trade while rueing the state for regulating Sunday work. Increased oversight would tighten the trade around those most moral and make it harder for the unscrupulous to have a secret menu. For many barbers, the secret menu was drugs, vapors, gambling, opium, or prostitutes.

A town was a gateway to the city; the barbershop a gateway to vice.

A door within a door. Occult. A black hole.

Here is a posting about a barber shop in Ottumwa serving as a front for cock fighting:

Iron capitalism had necessitated organized labor. The breaking of organized labor by the bosses had necessitated organized crime. Secret society vs. secret society. To be a frontier barber was to be pushed and pulled by too many sources external and internal to the barbering community. The workers, the bosses, scab labor, untrained barbers, puritans, prudes, and the antecedents of the mafia. We should guess most barbers made a clean living simply harvesting the beards and boils of men. Others were perhaps more adventuresome.

LaMorte Spencer was a vibrant member of the Muscatine Barber’s Union from the early days, when the union made simple demands of themselves and other barbers meant to improve the lives of all who plied the trade. Limiting hours of operation to those agreed upon, for instance, meant a more equal share of the profits of what is a necessary trade. The tragedy of the commons undone by compact.

Some years later and more sinister forces are at work. Further barber postings in this period concern the growing rift between union and non-union barbers. Union barbers work in concert, setting shared prices and hours. The non-union barbers would disregard such standards, posting lower costs or later hours and drawing profits from the union.

This schism overlaps somewhat with the existing feud between chivalric and schooled barbers. Many of the union barbers were the old tradesmen or their apprentices; the non-union shops being more friendly to the shakier handed greenhorns.

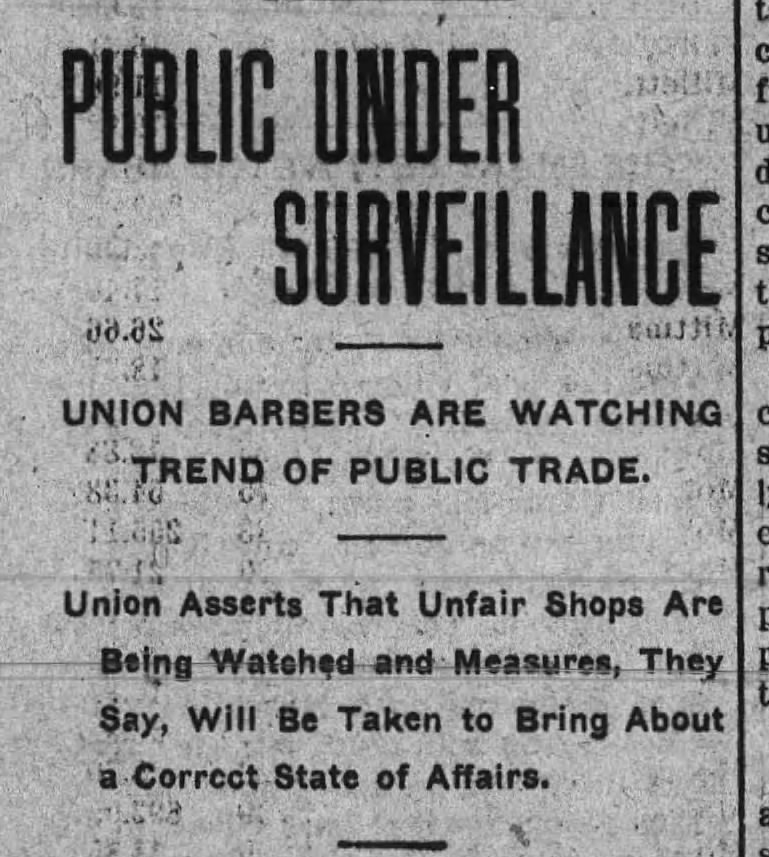

Eventually the scene in play is one of mafia-esque warnings between the groups. It is surprising this was even posted:

It was a dicey time for organized labor with a high potential for violence.

In 1904 our man Spencer was chosen as emissary to Louisville for a Barbers Labor Convention, reporting back to the Muscatine Journal that the city was “dirty”. His descriptions suggest a rivalry left from the Civil War, perhaps grown over with weeds and time yet still begrudged.

Again in 1905 he was tapped to attend the Federation of Labor Convention. This is a much larger rendezvous than his tryst to Louisville the year prior. The Federation of Labor would become the AFL-CIO, a massive labor union still in operation. This convention was held directly across the river from Omaha, in Council Bluffs, Iowa; both locations notorious for their underworld machinations and vice districts.

LaMorte was chosen to represent organized labor in Muscatine on the whole, not just barbers. A nice notch in the belt for a committed lifelong labor organizer.

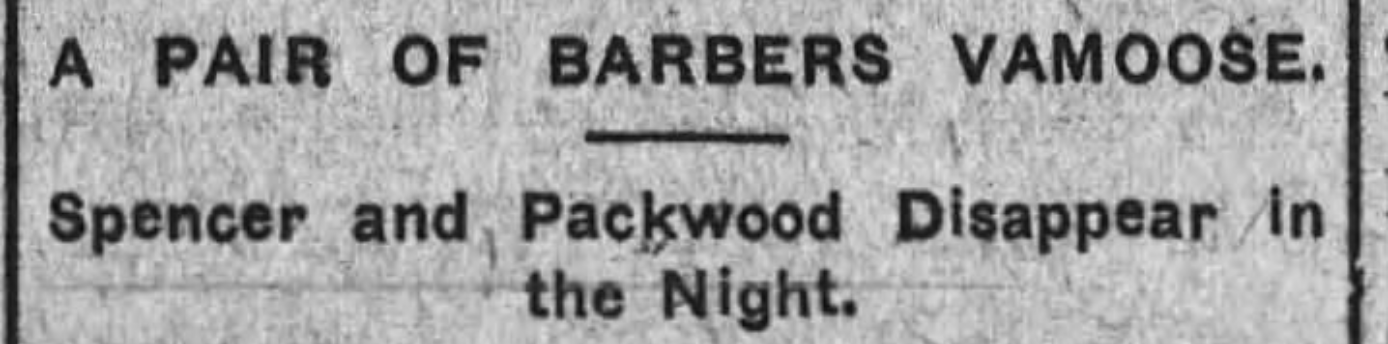

So it is of some surprise when we find he chose instead to “vamoose” from Muscatine and a chair at Art Welch’s Panitorium just four days prior.

LaMorte Holley Spencer had his life well ordered in early 1905: a respected barber, leading member of the labor movement and the union.

With spouse and child he abruptly left this life behind.

When we find Spencer again he has spent the rest of his life in Chicago, having given up the barber trade entirely in exchange for a lifetime of working as a ticket agent for the railroad.

Something must have spooked him.

The timing is incredibly suspect. The language of the “vamoose” article equally so. Whatever debts he relieved by removing himself from Muscatine were likely not monetary; one cannot typically pay off a monetary debt by leaving town. Someone owed someone something.

Yet more intriguing is that Chicago in May of 1905 was in the midst of a broad and violent labor struggle. For years the kettle had been working toward a boiling point; now the Teamsters, in charge of all shipping and moving of goods for the city of Chicago, had joined in sympathy strike a smaller outfit of tailors. They had shut the city down. Widely followed, this story was well covered in papers at the time. Violence against “scab” labor on the daily. Riots that consumed whole blocks. Death. Anyone who read the papers would have known what was occurring on the regular.

LaMorte is a riddle. What could happen to a successful and embedded union barber to send him two hundred miles away, to abandon the trade and his former life altogether? Did the grip of regulation finally crush him, or did he come up against some underworld juggernaut he could not contend with?

Rex William Packwood was no stranger to vamoosing.

Rex is the main character. He’s a scoundrel, a barber, a con-man, and a gangster.

Some people live their whole lives and barely scratch their names out. Others are so well recorded it can astound. Many times these clues sit in photo and ink, even digitized but not ordered. Needles in haystacks most certain. When we apply all this modern technology to the hay we get a bag of disconnected hints; several incomplete puzzles. We have to guess.

Apart from the direct records of Rex, we have access to a library of random facts concerning those who walked beside and around him, and likewise the places he lived.

We can fill in the edges of his life as if we are rubbing a worn stone message into view with paper and charcoal. Some of these characters play main roles in the narrative, others play bit parts and then fade behind the proscenium into their own unrelated adventures. They each expand our understanding of who Rex was.

Let’s start with his parents.

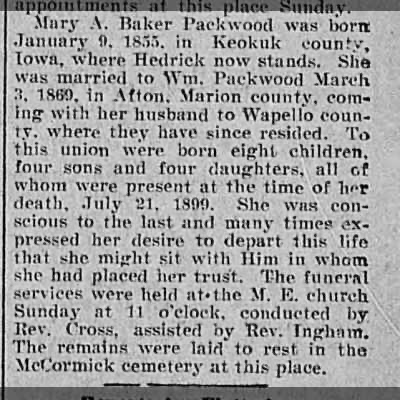

William Samuel Packwood II married Mary Alice Baker in 1869. He had come to Iowa as a child, brought by his father and uncles shortly after Iowa had been appropriated for settlement. They had lived in Indiana beforehand, in both cases the family expanded into newly acquired territories essentially stolen from the displaced indigenous people.

It was a life of mud and death with zero access to comfortable resources. William would have been a hard man, however kind or unjust. He was a farmer of commodities like buckwheat and also kept horses and deer. He was probably a Freemason, like his father and grandfather.

They married when he was 24 and she 14. She came from the eastern Iowa Baker family, a large and comfortable family of farmers. She would provide William with eight children over the next 30 years before dying in 1899, surrounded by all her family and praising the Lord.

Rex was born William Rex Packwood, with “Rex” a stand-in for III, on January 1, 1882. He was the third of what would be eight in a prolific family on the edge of the frontier at a time of great change. The railroad, that great iron beast of fire and smoke, had come to Iowa in the same generation and proceeded to smite the idyllic peace of the petit kingdoms of the plains.

For generations now the farming clans had prospered over the dominated land, survived many a hard winter and reproduced prodigeously. In the Packwood family, Rex was one of eight children, his father the youngest child of nine, and his mother had seven siblings. Massive families made some modicum of sense when the expectation was death before adulthood.

The train brought change.

The train brought life.

Medicine, hygeine, solvents, vapors, alcohol, media – and a deluge of people from the bricky east still high on the hog from justly winning the Civil War some decades prior. Iowa had always been for the Union, now the industrial veins spread easily over the sleepy farms. Industry would come to dominate the land and usurp each and every tiny kingdom. The Iowa farmer switched from farming for sustinence to farming commodities for trade. One of many necessary adaptations to centralized capitalism the kingdoms had to make. In the prior situation the farmer would surely perish without a successful crop; in the latter it was crucial to ensure maximum profits.

The posting below discusses William sowing buckwheat:

The life that Rex was born to inherit was crumbling into dust. For decades it had been a clear and simple pattern of living – farm the land, reproduce, survive. Birth control not really a concept. As a child, Rex would have dreamt of his own farm, his own wife, his own animals, his own future as an American lower-case k king.

Rex, afterall, means king.

He would have spent most nights of his youth sleeping on rough wooden boards over a dirt floor in a one room cabin with his seven brothers and sisters, mother and father, and whatever other soul may have been blown into range of the fire’s heat on a cold night. Maybe the animals if the weather was bad enough.

Iowa vernacular housing at this time was also in a period of transition. The railroad brought the rigid uniformity of precision to the character of the frontier. Homes like the one Rex would have grown up in were built a decade before. They were rough hewn log affairs chinked with mud and manure, lacking for windows and almost universally with a southern facing open door for double service as a clock.

Beyond old-timey. Barbaric.

The train brought high tolerance equipment and improved materials; Rex watched beautiful homes spring up around his moist planks. Streets became straight and level, pipes buried, the horror of the outhouse replaced by the luxury of the interior bath. Gas lamps. Furniture. Motor cars. Ratcheted escape from the dirt floors of the previous world.

This was a twilight time between periods and Rex was a twilight character, he belonged in neither the previous nor coming age. He came of age witnessing a massive societal shift from the stone hearth and wax paper windows to perfumed water closets and wallpapered parlours. We should pity his generation for they were obviously torn asunder by these forces. Incapable of fulfilling their birthrights they were doomed to wander in lust for a world not yet born. .

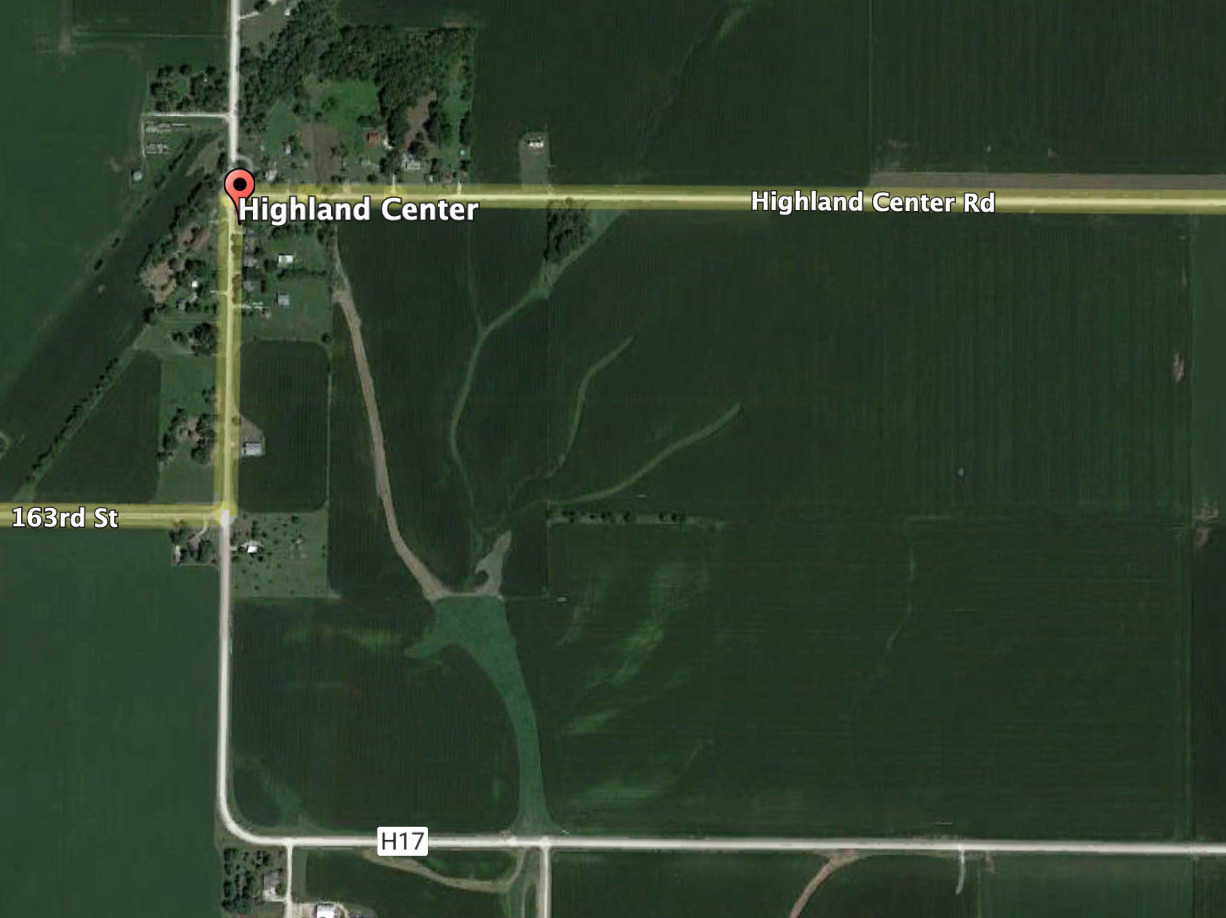

The original Packwood farm house is gone now but the rough rock foundation and hand dug well remain, obscured by a triangle patch of trees in a sea of industrial farmland. The busy previous life of the rail road marked by patchy concrete and abandoned right of ways scratched into the ground. The iron is gone but some scars are permanent.

Highland Center today is a crossroads not sleepy but asleep. Despite that, a surprising amount of traffic slips down the gravel of Highland Center road as a sneak between the suburbs that have colonized the farmland.

In the 1880s it was an active farming hub, one of thousands strewn along the happenstance of the railroad map to serve the iron master. Here they loaded the train with buckwheat and corn, served it the water it needed, and took from it the bounty of goods they grew each day to desire yet more.

The city lay torturously a scant ten miles by train directly to the southwest. Probably a half hour trip. Ottumwa was a vibrantly seedy commercial hub at the crossroads of the river and the railroad. A gateway to anywhere.

This is a tease hard to resist. Weigh your options and see the old crumbling world of manure and toil juxtaposed against a gaslamp street full of sharp suits and loose women. The easy money of the gambler. Laughter drifting over the aroma of cigar and sex.

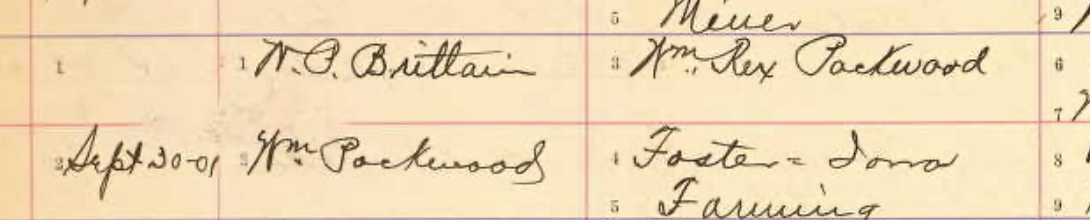

In 1900 Rex is listed in the Iowa Census as a Farmer, under his father and older brother as the same. Still in Highland Center. Primed for a lifelong course of earth and husbandry.

In 1901 he marries local sweetheart Mittie Brittain. Her mother was the daughter of old man Waugh, of Waugh’s point, so named for the point of trees where the forest terminated and the plains began. He sold his land to rail speculators who later planted the still standing railroad town of Hedrick, Iowa.

The newspaper announcement states Rex and Mittie are living in Hedrick, presumably with the Brittain family, just six miles northeast of Highland Center. Rex’s father, William, has moved to Foster about 45 miles southwest where he runs a deer farm and keeps racing horses for breeding. Their marriage record reflects the Foster address.

Rex and Mittie are both nineteen years old and married. Their prescription for life carved in the bark of a dying tree. Farm the land. Grow a family.

Their first son is born in 1903. Curiously he is born in the hospital at La Plata, Missouri, about 90 miles south of the Ottumwa area. Without surrounding records we can only ponder the variety of reasons to give birth such a distance away. In 1903, 90 miles is quite a trip.

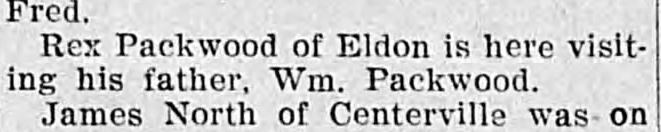

Two months later in March, Rex visits with his father back in Ottuwma. This might be a coded statement, as a “visit” in 1903 is more unwieldy than today. Mittie and three month old Harold are not mentioned and seem to have been left at home. This is the last we hear from Rex the farmer.

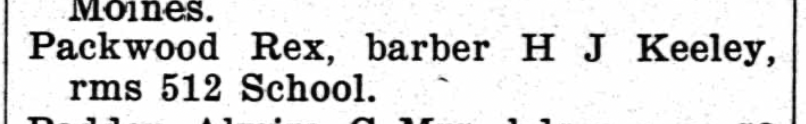

It’s 1904 and suddenly Rex is a barber in Des Moines, Iowa. The change is swift and permanent. He will list himself as a barber for the rest of his life.

For Rex to be listed in the 1904 directory, he would have had to arrive in Des Moines no later than the tail end of 1903. This might align nicely with his visit to his father in March. Perhaps his life on the farm was not working out and he needed advice for a change.

In Des Moines he worked for H J Keeley, a master barber that ran a shop with a revolving cast of second-chair barbers in what was probably a master & apprentice situation. Keeley kept shop in the lower level of the same building that housed the Trade Association Hall. This would have provided him and his barbers with a steady of flow of beards to reap and labor connections to exploit.

We should assume Keeley ran a Union Shop, and that Rex was a Union Barber. The evidence suggests that Rex earned his razor working for Keeley in Des Moines. Note also that Rex spends a year in a city, renting a room, eating fried chicken, drinking champagne and cavorting with whatever roustabouts were rousting about. Keeley ultimately went bankrupt in 1907 and moved to California where remained a barber for life. California seemed to call to all these characters like paradise calls the pious.

To be a barber on the frontier was to carry civilization in a satchel. The shaved masses were so much different from the wild mob when removed of their whiskers. For Rex it was a conscious choice against farming. The farmer has dirt under their nails, the barber gives manicures. Opaquely worlds apart.

His address in Des Moines at 512 School was a flop in a walk up flat, now an onramp of I-235. When the Eisenhower Corridor, the interstate highway, was built it quite often was used to excuse the obliteration of “blighted” neighborhoods and to create classist and racist walls and buffers in cities.

Rex seems to have preferred the blight, the red light districts, and the fonts of vice and graft. A refrain in his life is that many of his former homes have been razed to the earth. They were all routinely within six blocks of the prostitutes, alcohol, drugs, and gambling.

His time in Des Moines ended as suddenly as it began. The next year in 1905 we catch him in Muscatine with Mittie and Harold. If they were with him in Des Moines it remains unrecorded. A good guess would be that Rex, distasteful of being a farmer, went to learn the barbering art in Des Moines, and now so beknighted had moved to Muscatine to settle into a placid life of farming beards.

In Muscatine they live at 306 E. 3rd. Today a parking lot.

The pattern that starts to show itself is that Rex can’t stay put. Time and again he vamooses. We can only speculate as to his motivations. A sour marriage, the stress of raising a child, or the rote moisture of the farm. Tonsorialism a crude doorway out of the life he inherited.

It’s 1905 and Rex has fallen in with LaMorte Holley Spencer – the achieved and respected barber, union man, and labor organizer. Together they cross paths with inscrutable Art Welch; an inflection point. A chemical reaction. Whatever monster shook LaMorte toward a life of contented labor in Chicago sent Rex a different direction. The Union. The Masons. The Socialists. The Puritans. Some anonymous demon. Take your pick.

In May Rex famously vamooses. The article at the head of this chapter takes pains to explain that Spencer was a good man, while there is no similar caveat for Rex. Four days later a printing appears in the same paper that Mittie and children have gone to Davenport to live with Rex. An oversight in printing, or had they already a second child otherwise unrecorded?

Davenport, Iowa in this time was a raucous antediluvian Las Vegas that rivaled Ottumwa. A move to Davenport was a step toward vice, not away. Davenport would have equal portions of beards to shave and temptations to embrace and both in ample easy servings.

Three months later in August, Mittie is back in Ottumwa, “visiting” her parents. Remember “visit” might mean more than an afternoon.

In October a listing appears for undelivered mail for Rex in Davenport.

The impression is that Rex and Mittie are adrift for a season. Not sure where they are heading, not sure where they have been.

LaMorte Spencer was a raised Master Barber, accomplished and connected. Whatever shook him also shook Rex. Threats from authorities? The Black Hand? Socialists? Puritans? Other Barbers? The sun went down one night and LaMorte ran away from the barber trade and Muscatine and settled in Chicago somewhat placidly.

Rex took the opportunity to remove himself from Muscatine to Davenport, but their stay in Davenport is short lived.